By ‘airdrop fundraising’ I refer to situations in an educational context where students are asked to give money, or students lead others in processes of donating money, without students being involved in any wider process of change or journey of understanding.

I think it’s clear that as with all activities conducted in an educational context – and this could equally refer to choices of food made by catering or use of energy within schools – that we need to recognise that students will be learning something from the activity. Therefore, we need to ensure that the activities we engage students in meet our own intentions in terms of outcomes; just as with learning a new mathematical concept, students need building blocks towards the concept, and progression following it.

The ideas shared here have been informed by my mix of experience of a leadership role overseeing service and partnerships at a large IB school and through my role as CEO/Founder of EduSpots which has involved significant school partnerships work. I also lead the School Community Action Network, where teachers across the UK explore improving practice in service learning to advance impact for all.

What are our educational aims?

So taking a step back, why are we including ‘service’ or ‘change making’ activities in our school curriculum or co-curriculum? To state the obvious, for many, the inclusion of this within school systems stems from a genuine desire to drive sustainable and deep changes in our communities, and the world more widely, often with the focus of addressing various inequalities that our students and staff believe are unjust.

Through ‘service’ activities (a later post will explore some issues with the language of ‘service’) we are aiming for a mix of the following aims:

1. Community impact

We aim to work in partnership to play a valuable role in creating a sustainable and valuable impact upon communities that we are working with.

2. Grow understanding and skills

We want students, and the wider community, to learn about the social inequalities we are addressing and why they exist, and the change making process more widely, picking up new skills, knowledge and values during this journey that will equip them to make further positive contributions in the future.

3. Challenge inequitable systems

Less often cited, and controversial for some: we want to challenge systems in society that reproduce inequity, including the power imbalances often implicit in relatively more privileged people making choices that considerably affect the life opportunities of others without sufficient research or engagement in the charity’s activities, despite their own life-changing nature.

These three aims are all interconnected and are together ultimately required to solve the problems we are seeking to change and to create a more equitable global society: we simply cannot drive sustainable long-term impact without advancing skills and understanding, or changing systems.

So what are the possible harms implicit in engaging purely in transactional fundraising processes?

Firstly, I think that it can give weight to the idea that solutions to problems can always be solved through financial transactions. Students are easily habituated towards different ideas, and this might pass on to their wider life in terms of creating solutions – ultimately asking someone else to solve the problem!

Secondly, a purely fundraising based approach can disconnect students from the issue itself – many of the world’s greatest challenges are in part caused by the every day actions of every day people, whether through consumer choices, political engagement or wider attitudes. If students always fundraise as a first step, there is no chance to consider their own role in creating or addressing the inequality.

Linked to the above two points, this approach to creating change can further cement divisions in between different groups of students, rather than giving students a meaningful chance to explore what might connect them or learn more about the role that affected communities might play in leading the change within the charity’s model.

Ultimately, involving students in fundraising without any wider education further reproduces the disproportionate power that rests in the hands of those with relatively more money.

So how can we engage students more in understanding the change that they are leading, deepening their engagement in a process?

1. Asking students to research the cause they are supporting and exploring diverse methods for creating change. Asking probing questions such as: is fundraising the best way to support? What alternatives are there? Could advocacy or simply sharing understanding be a more effective alternative? How can you learn more?

This is key to also avoid a sense that student are being ‘airdropped’ into a fundraising activity or volunteering opportunity, without understanding the concept, which could even make some students feel used in the process.

2. In this process of investigation, we shouldn’t be afraid to ask students if they doing anything through their every day choices that might be contributing to the issue, recognising the interconnected nature of our universe? What else might they need to learn to be sure of this?

3. If we are fundraising for a charity, we need to consider how students are currently choosing the charity. What criteria might we think are important: a) for impact? b) For learning?

Perhaps we can even ask some student leaders in the area to create a handbook for choosing a charity, looking at areas such as their methodology, expenditure, impact and staff team experience.

4. Enable students to be an effective advocate for the cause – I’ve often found that students can get embarrassed when asked ‘What is this cake sale in support of?’ by their peers or teachers.

Again, students need support, perhaps with a simple advocacy framework. Here’s an example: 1. Explain the problem and why it matters (20 secs), 2. Explain the solution (20 secs) 3. Explain how the world might be different as a result (20 secs). If students are introduced to this sort of framework in their earlier years, they will gain in confidence, and by the Sixth Form be powerful Ambassadors for the causes they care about.

5. Ask them to reflect on the impact afterwards, embedding impact reflection into the educational cycle. Perhaps students can even create an Instagram reel that is shared, or create their own impact newsletter.

Just as with an English essay, students need clear feedback on their approach, with constructive critical feedback vital for progression. In this process, it’s important to think twice before making the total raised the key thing that is praised – some students may have less wealth in their communities than others, or have created further impact through strong advocacy in the process, and similar.

Students ultimately usually want to make the greatest difference, too, so being more critical in their approach is helpful to their own goals.

I think these areas apply whether the cause is something a student has chosen to support through a student-led project, or whether the charity is something the school is building a longer term relationship with through a service/partnerships programme. It’s often quite a balance when planning a school fundraising strategy, to enable a mix of supporting long-term partnerships and support student-led initiatives.

My personal bug bears relating to this topic that partly prompted this article..

- Students leading events ‘for charity’ without mentioning what the charity does.

- Students picking charities through quick google searches, even for major fundraisers.

- Students being too embarrassed describe the cause and its importance to their peers when asked.

- Students never checking the money has been sent or truly engaging with what the impact is.

- Rewards for fundraising – e.g. Students promised pizza or special treat for most money raised etc.

More unpacking of these in future posts!

Do we/I expect too much?

Some may suggest that I expect too much from young people, and that engaging students in this process may put some students off acting. Indeed, I agree, it may put some students off who were looking for any easy win for their UCAS, D of E or CAS. Is this a loss?

Well, you might quickly suggest that this may lead to less money for the charities; however, my long-term experience has shown me that teachers engaging with this deeper process in an encouraging and inspiring way, and enabling longer-term engagement and partnerships work can lead to considerably more investment from the students, leading to more money donated and a longer term commitment to leading change, driven by compassion.

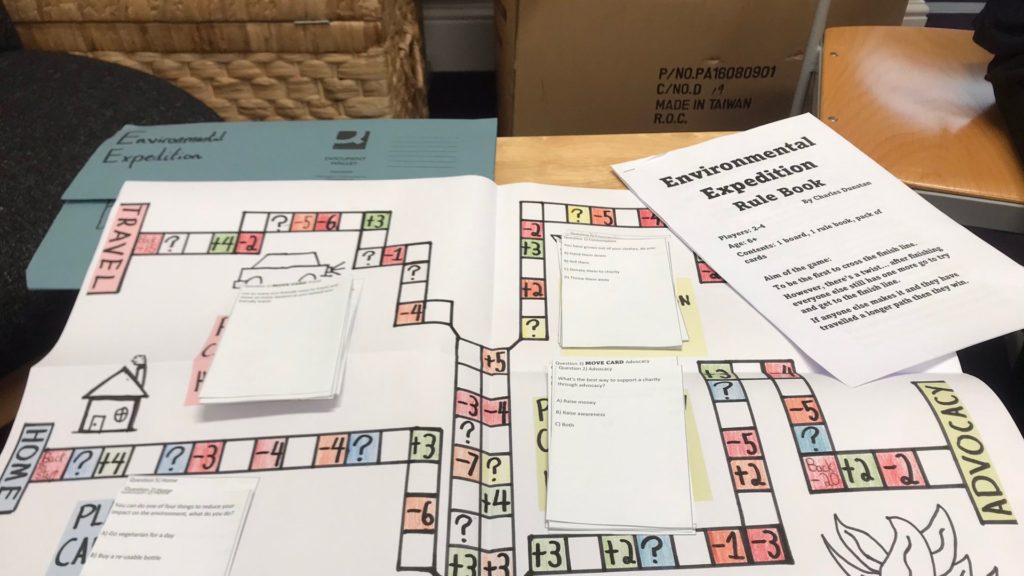

As shown by this example of an ‘environmental expedition’ awareness board game created by one year 8 student who could have fundraised for an environmental charity, students recognise that the learning process involves all of us for truly sustainable and inclusive change to occur.

For EduSpots, I would definitely rather have one fully engaged Ambassador (quick plug: students can sign-up to our programme here!) for our cause then a group of mindless fundraisers. And this deeper connection, is what our global and local society desperately needs.

What do you think? Do you disagree with anything? What might I need to rethink or explore further?

What other topics would you like me to write about? Add in the comments!