Ahead of reading this analysis, please read part 1, part 2 and part 3 of this series of blog posts which offers an introduction to the topic and theories.

Through these posts, I exploring the issue of exporting/importing western fiction to Ghana or indeed other countries with a previous colonial relationship, with a view to informing EduSpots ongoing strategy in this area.

This post focuses upon identity. Postcolonial theory and the capabilities approach are used as tools within the process of interrogation of key ideas and issues.

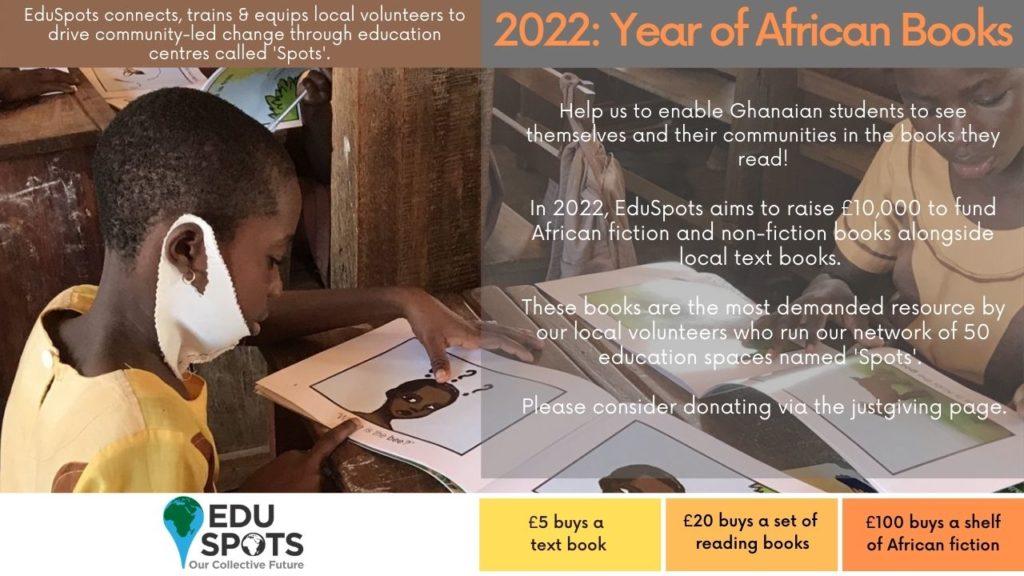

The cover photo is taken from the EduSpots website.

Postcolonial analysis

The postcolonial approach would highlight the fact that reading western fiction rather than African fiction in a local dialect, or in English, might lead to a confusion of identity. Identities are constantly reformulated by the constant power context in which they exist, and humans at any age are so often unaware of the ‘hands that are writing us’ (Andreotti, 2011:222).

It is clear that relevance to one’s own situation and community is key. There has been much criticism of the educational leaders in previously colonized states taking too long to move syllabi away from Euro-centric content towards an African-focused syllabus. Thiong’o argues that this delay in Kenya led to a separation between a child’s education and his home environment, where ‘bourgeois Europe was always the centre of the universe’ (Thiong’o, 1983: 17). Adjei (2007) stresses the extent to which the Ghanaian curriculum was suffused with knowledge that was irrelevant to his own environment, giving the example of Geography lessons requiring him to study rivers ‘seven thousands miles away from his Ghana’, and History lessons that failed to acknowledge the existence of any Ghanaians who played a positive role in the country’s past. The oral tradition that was a central part of his childhood education was left out of the curriculum, and the lack of relevance and reference to local traditions led Adjei to a sense of alienation, a crippling loss identity and a lack of national pride (Davison, 2017a, Dei, 2000). In Nervous Conditions, Dangarembga (1988) describes the relationship between a girl and a relative who has adopted white ways, who she struggles to interact with. The implication of this story is that through reading western fiction many Ghanaians might start to feel what Fanon recognizes as a ‘hybridized split existence’ (Young, 2003) whereby they try to live as ‘two incompatible people at once’.

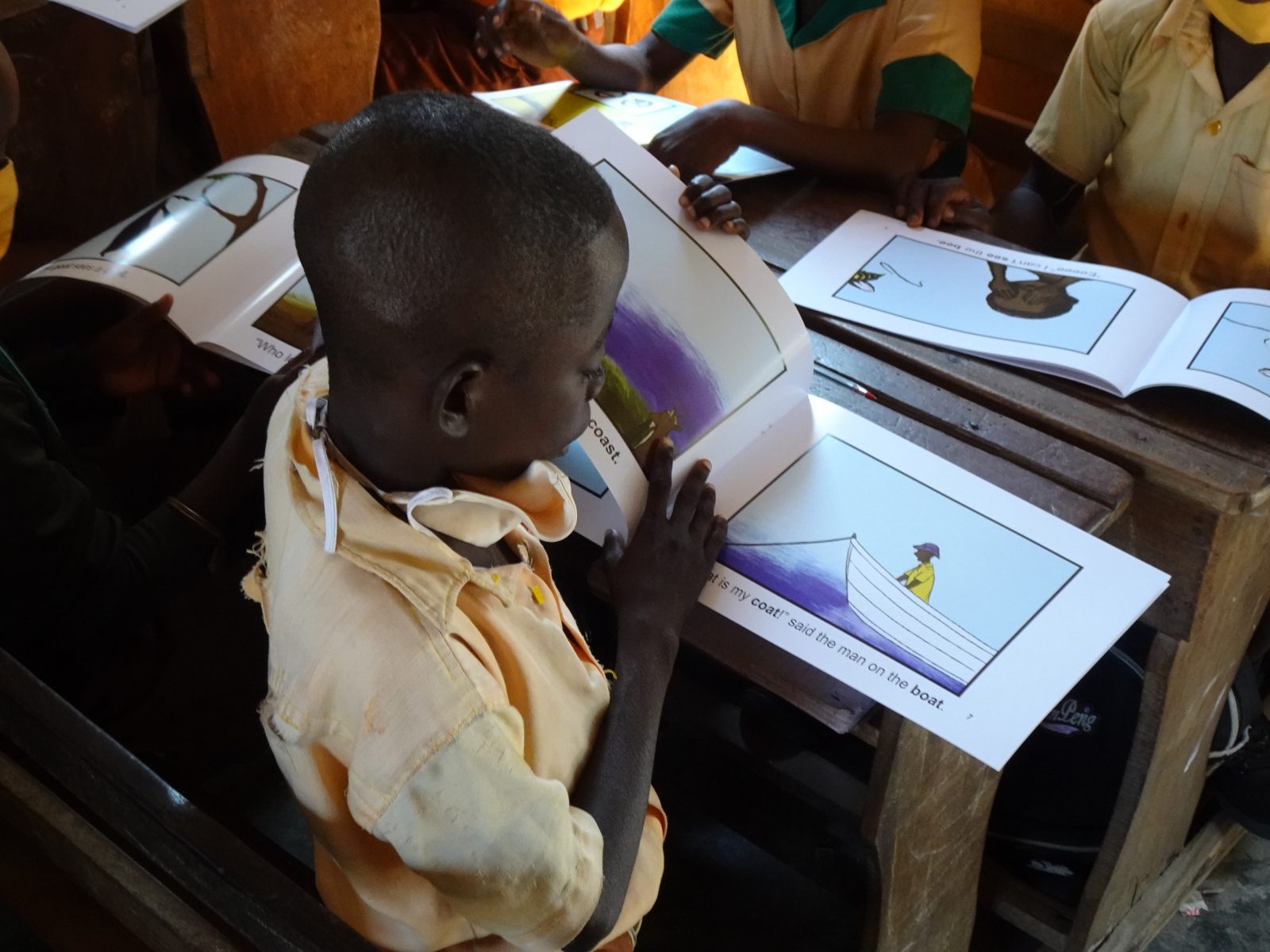

It is clear that if pupils are reading books that only contain white role models, that this may further consolidate the notion of white supremacy within Ghana. For example, statistics from a study by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center found that in a sample of 3600 children’s books published in the US, only 3.3% were about African-Americans. Indeed, Adichie states that she ‘did not know that people like me could exist in literature’ (Adichie, 2009).This may reinforce the idea that pupils are to look to Europe ‘as her teacher and the centre of man’s civilization’ (Thiong’o, recommendations of the Working Committee, p7.). Bush and Salterelli (2003: 3) highlight that ‘children do not come to the classroom as blank slates’ – they have lived through their children adopting various practices, behaviors and attitudes; this it seems vital that these practices are represented in the fiction they access.

Freire (1968) argues through his notion of ‘conscientization’ that education should be used as a means to empower individuals, and sees active participation in creating syllabi as vital to the freedoms enjoyed by individuals. This could translate to Ghanaians taking an important role in not only choosing the material that they read, but also the importance of all Africans having the opportunity to contribute to the literary canon available.

Capabilities Approach

It would be impossible for a full set of freedoms to be given in relation to reading material in order to ensure that every socio-economic context in Ghana was represented. No matter what books are contained in a bookcase, there will always be some minority experiences, which are not represented and this could lead a loss of identity. However, as access to the Internet is improved, more pupils are gaining increased freedoms with respect to their ability to access knowledge that may be better tailored to the environment and upbringing of an individual. The African Storybook Project has been formed to create a digital library for early grade readers with stories that are uploaded by individuals and translated into various local African languages such as Twi (African Storybook Project, 2016). This will enable individuals to advance their learning in the mother-tongue independently from parents, which will assist with the later development of the ability to read in English (US Aid, 2014).

Others might argue that the very notions ‘capabilities’, ‘rights’ or indeed ‘freedoms’ are in themselves western ideas in part, and assumptions are thus being made in its implied usage as a universal doctrine; indeed, Andreotti points to less positive consequences of the concept of rights as an ‘alibi for… types of intervention’ by countries with ‘ambiguous aims or interests’ (Andreotti, 2011:212). It may also be seen that some Ghanaians do not prioritize freedoms, or indeed the preservation of identity, over the basic economic gains they might see their children make through investing time in improving their English through reading. Fanon himself asserts that the most important thing is the need for the redistribution of wealth, rather than various political debates (Fanon, 1963). Bhaskar (2008) might similarly suggest through his ‘critical realism’ that the underlying causal factors that lead to the lack of most important capabilities, need to be addressed first, before the preservation of culture is considered, which Maslow (1943) might suggest to be the ‘physiological needs’ of water and food. However, those using the libraries usually already have the basic requirements of food and water, and thus it seems that enhancing their education, in line with their context, is the best way to maximize their chosen capabilities, boost use of the facility and reduce a sense of alienation.

Recommendations

Some recommendation from this series of analysis for EduSpots’ work and the work of other organisations will follow in the next blog post, linking to EduSpots’ 2022 mission of ‘A Year of African Books’.

Bibliography

Achebe, C. (2010) A British Protected Education, ‘Politics and Politicians of Language in African Literature’. Penguin Modern Classics.

Achebe, C. (1975) Morning Yet on Creation Day. Published by Anchor Press (1975)

Adjei, P. B. (2007) ‘Decolonising Knowledge Production: The Pedagogic Relevance of Gandhian Satyagraha to Schooling and Education in Ghana’. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue canadienne de l’Education, 30 (4), 1046-1067.

Alderson, P. (2016) ‘Critical Realism and Research Design and Analysis in Geographies of Children and Young People’ Geographies of Children and Young People: Methodological Approaches, 2016,Evans, R. and Holt, L. (eds). Singapore

Andreotti, V. (2011) Actionable postcolonial theory in education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ayer, A.J. (1953) Language, Truth and Logic, Penguin 2001 edition.

Benhabib, S. (1992) Situating the Self. Routledge

Bentham, J. (1789) Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Dover Publications (June 5, 2007)

Bhaskar, R. (1975) A Realist Theory of Science, Verso 2008.

Brezinger, M. (1997) Language contact and language displacement.

Chakrabarty, D. (2000) Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial thought and history. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Davison, C. (2017) ‘Ghana’s metamorphosis: an examination of the success of Nkrumah’s education policies in Ghana (1951-1966) as a tool for peace building.’ Essay submitted for Conflict, Fragility, and Education in May 2017.

Dei, G. J. S. (2002) Schooling and Education in Ghana. International Review of Education September 2002, Volume 48, Issue 5,

Dent, F.V. (2013) ‘A qualitative study of the academic, social, and cultural factors that influence students’ library use in a rural Ugandan village.’ University Libraries, Long Island University

Elbert, Fuegi and Lipeikaite. (2012) ‘Public libraries in Africa – agents for development and innovation? Current perceptions of local stakeholders (Electronic Information for Libraries)’ Sage.

Fanon, F. (1963) The Wretched of the Earth. Penguin, 2001.

Feyerabend, P. (1975) Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge. First edition in M. Radner & S. Winokur, eds., Analyses of Theories and Methods of Physics and Psychology, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1970.)

Fanon, F. (1967) Black Skin, White Masks. Grove Press; Revised edition 2008.

Freire, P. (1976) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Penguin 1996.

James, P. (2006) Globalism, Nationalism, Tribalism – Bringing Theory Back In. SAGE, London.

Kant, E. (1785) Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.; 3 edition (June 15, 1993)

Loomba, A. (2005). Colonialism-postcolonialism. Oxford: Routledge.

Lyotard, J-F. 1979. La condition postmoderne: rapport sur le savoir. Paris: Minuit.

Mackintosh, M. (2007) ‘Making Mistakes, Learning Lessons’, Primary Geographer 62. pp19-21

Maddox, B. (2008). ‘What good is literacy? Insights and implications of the capabilities approach’. Journal of Human Development 9,2, 185-206.

Mauss, Marcel. (1990) ‘The Gift: The Form of Research and Exchange in Archaic Societies’ (1990)

Maslow, A. H. (1943) ‘A Theory of Human Motivation.’ Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-96.

May, S. (2012) Language and Minority Rights. Routledge.

Mill, J.S. (1859) On Liberty Longman; New Ed edition, 1998.

Mill, J.S. (1863) Utilitarianism. Hackett Publishing Co, Inc; 2nd Revised edition edition (1 Mar. 2002)

McCowan, T. and Unterhalter, E. (2015) Education and international development: an introduction. London: Bloomsbury Academic Press

Mincer J. (1981) “Human Capital and Economic Growth” Working Paper 80, National Bureau of Economic Research. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w0803.pdf (accessed 20/05/2017).

Nussbaum, M. (2010) Not for profit. Why democracy needs the humanities Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nussbaum, M. (2011) Creating capabilities. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Nkrumah, K. (1964) Consciencism. Monthly Review Press (January 1, 1964)

Said, E. (1980) Orientalism. London: Routledge. pp 322-8 (‘Orientalism Now’ is also reproduced in Lauder, H. et al. (2006) Education, globalization and social change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.)

Said, E. (1993) ‘Representations of the Intellectual’ The 1993 Reith Lectures

Sen, A. (1999) Development as Freedom. OUP Oxford; New Ed edition (18 Jan. 2001)

Sen, A. (2009) The Idea of Justice. London: Allen Lane Penguin

Skutnabb-Kangas. (2000) Linguistic Genocide in Education – Or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights? Mah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Singer, P. (2011) Practical Ethics. Cambridge University Pres

Smock and Enchill. (1976) The Search for National Intergration in Africa

Spivak, G. C. (1988) ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’. In C. Nelson and L. Grossberg (Eds), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. x, 738 p). Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Some, M. P. (1994) ‘Of water and the spirit: Ritual magic and imitation in the life of an African Shaman.’ New York: Penguin Books.

Stirrat, R.L. and Henkel, H. (1997) ’The Development Gift: The Problem of Reciprocity in the NGO World’.

Takayama, K., Sriprakash, A., & Connell, R. (2015) ‘Rethinking Knowledge Production and Circulation in Comparative and International Education: Southern Theory, Postcolonial Perspectives, and Alternative Epistemologies.’ Comparative Education Review, 59(1).

Dangarembga, T. (1988) Nervous Conditions. Zimbabwe Pub. House (1988)

Tomasevski, K. (2001) Right to Education Primers No. 3: Human rights obligations: making education available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable. The Right to Education Project, Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA). Accessed at: http://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/Tomasevski_Primer%203.pdf

UNESCO, (2016) ‘Education for people and planet: Creating Sustainable Futures For All’. Global Education Monitoring Report, Paris, UNESCO – available on the UNESCO website.

Wa Thiong’o, N. (1986) Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Heinemann (2005)

Wa Thiong’o. (1969) Homecoming, London. P145

Wittgenstein, L. (1953) Philosophical Investigations. Wiley-Blackwell; 4th Revised edition edition (6 Nov. 2009)

Young, R. (2003) Postcolonialism: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young and Muller. (2016) Curriculum and the Specialization of Knowledge London Routledge.

Online Resources

African Storybook Project http://www.africanstorybook.org/index.php (Accessed 29/05/17)

The Danger of a Single Story, Adichie. Ted Talks, 2009.

https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story (Accessed 29/05/17)

Book Aid International: Kenya.

https://www.bookaid.org/countries/kenya/ (Accessed 29/05/17)

Books for Africa: About:

https://www.booksforafrica.org/about/about-bfa.html (Accessed 29/05/17)

Butler, E. ‘The Man Hired to Have Sex with Children’. BBC News, Malawi.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-36843769 (Accessed 29/05/17)

Davison, C. ‘Projects: Abofour Library’.

1 Comment

[…] draws the analysis from the previous posts exploring the elements of language, epistemology and identity together in some conclusions, ahead of relating this to EduSpots’ organisational strategy for […]