Ahead of reading this analysis, please read part 1 and part 2 of this series of blog posts which offers an introduction to the topic and theories.

Through these posts, I exploring the issue of exporting/importing western fiction to Ghana or indeed other countries with a previous colonial relationship, with a view to informing EduSpots ongoing strategy in this area.

This post focuses upon epistemology. A fourth post on identity will follow. Postcolonial theory and the capabilities approach are used as tools within the process of interrogation of key ideas and issues.

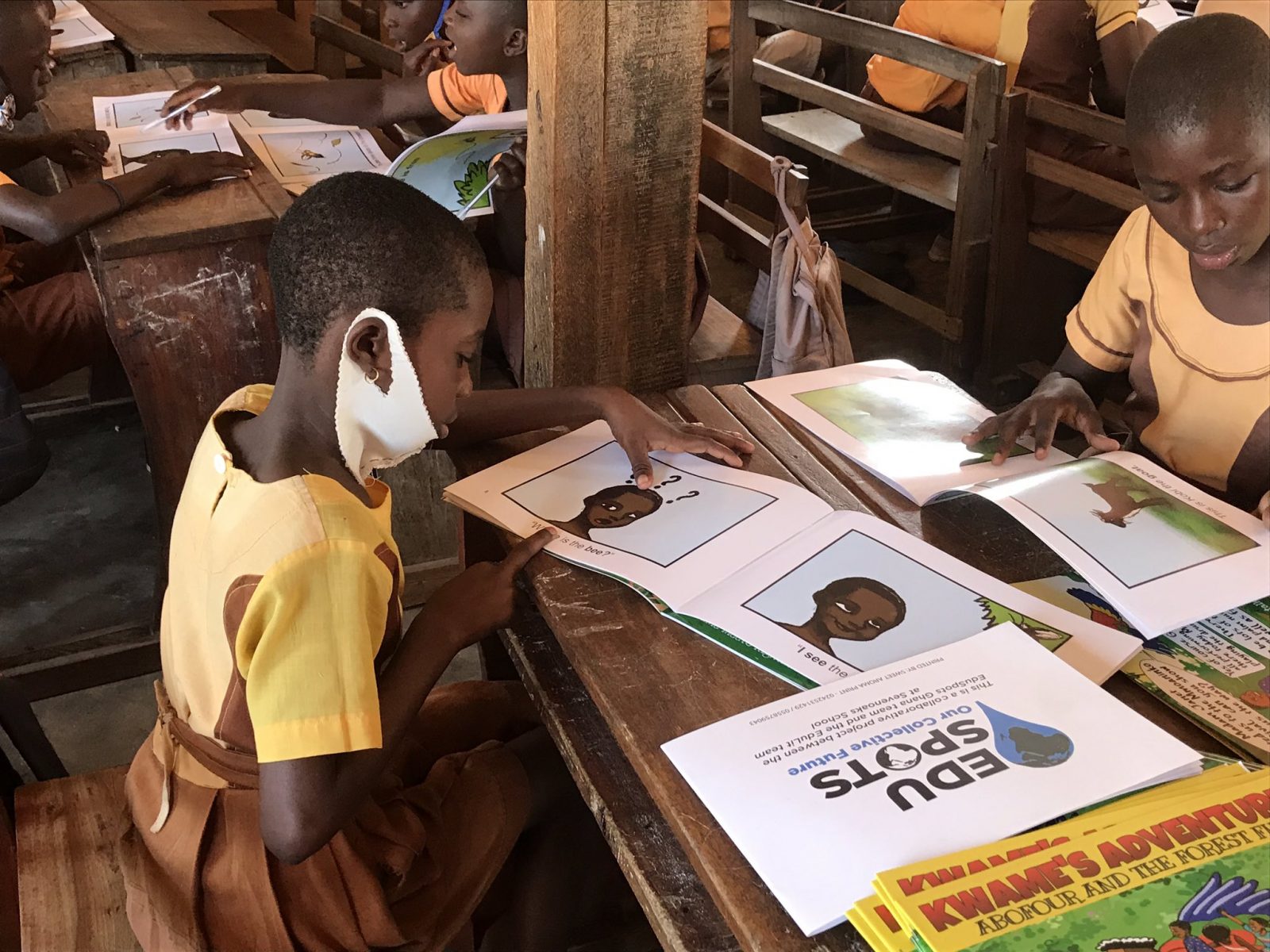

The cover photo is taken from the EduSpots website.

a) Postcolonial Analysis

It is clear that there are numerous epistemological implications of importing western fiction to educational projects. Spivak highlights the importance of giving subaltern experiences a voice in literature (Spivak, 1999), applying Foucault’s term ‘epistemic violence’ to describe the removal of non-western epistemological lens’ on the world. Indeed, ‘How we see a thing…is very much dependent on where we stand in relationship to it’ (Thiong’o, 1969), and therefore it seems wrong to present fiction to children which presents them with what Adichie might term a ‘single story’, suggesting that if you ‘show a people as one thing …that is what they become’ (Adichie, 2009). Fundamentally, postcolonial thinkers would want to steer the direction of fiction within African towards that which places ‘Kenya, East Africa, and then Africa in the centre’, (Thiong’o, 1969).

However some might suggest, contrary to the postcolonial canon, that some metanarratives are more valuable than others, and that it is possible to assert certain ways of knowing as superior to others. If we fail to assert an epistemological hierarchy we might be left in a slippery slope towards the position of postmodernism, which Lyotard (1979) defines as ‘incredulity toward metanarratives’, and is epitomized by statement that ‘anything goes!’ (Feyerabend, 1975). It is clear that to avoid the disorientated position of postmodernism, critical analysis is vital to determine which truths seems to cohere with other beliefs that we hold to be ‘true’ within our ‘language game’.

Andreotti directly addresses the difficulty of a possible shift into absolute relativism, suggesting that ‘truth and morality are contextually defined’ and therefore a critical examination of the contextual ‘baggage’ of knowledge production processes is vital (Andreotti, 2011:215). Others might reinforce the importance of variety, in order for pupils to be able to compare the views and lifestyles presented therein to their own; clearly offering only western fiction will give pupils a bias system of reference, and undermine the process of open critical analysis.

Santas goes further in highlighting the need for global cognitive justice, asserting the urgent priority for all actors in the world to reassert the epistemological diversity present, and bring back local wisdom that has been marginalized. She highlights the faults with much western imperialist knowledge, such as noting that capitalism has ‘ecological limits’, rejecting what she terms a Cartesian assumption that the ‘res extensa’ (extended thing) of the environment is ‘unconditionally available’ for humans beings holding the ‘res cogitans’ (thinking thing) (Santos, 2014: 23). Under this view, it would seem that the NGOs exporting books to Ghana are somehow complicit in this ‘epistemicide’ – whilst not purposefully excluding the local epistemology, through its very absence in both the created library, and the process, local knowledge is subject to ‘epistemic violence’ (Spivak, 1999).

Much has been written with respect to the difference in knowledge systems in question: for example, indigenous cultures tend to rely heavily on metaphors and stories as a means of imparting knowledge (Andreotti, 2011: 221). Cajete (2000) highlights the difference between a ‘rationalist’ mind and a ‘metaphoric mind’, suggesting that the metaphoric mind constantly creates stories ‘from collective subconscious or semiconscious images’. Dion-Buffalo (1990) explores the impact of metaphors working through shifting moods, and creating mental change through being ‘seeds of thought’. It seems vital to respect that knowledge is diverse: it is varied in both its form, and in the process by which knowledge is gained. Indeed, it is important that alongside the provision of African fiction, libraries also create book clubs where oral storytelling traditions are preserved, and an element of Ghanaian play is continued. In the first library established by Reading Spots in Abofour, pupils meet at 7am each Friday to critically examine books and their covers, share riddles, and play a literary version of ‘truth and dare’, all run by a local school’s library Prefects (Reading Spots, ‘Abofour Library’).

Furthermore, pupils are usually aware of books having a Western origin. Even if they do not arrive with a charity’s stamp and a ‘donated by’ sticker, Ghanaian books have a different look and feel to them, due to the different designs, paper, and fonts used by Ghanaian publishing companies. Stirrat and Henkel (1997) analyse the impact of NGOs giving ‘gifts’ to lower-income countries, following Mauss, in suggesting that ‘there is no such thing as a free gift’, and that gift-giving can only reaffirm difference, even in those NGOs which emphasize the importance of partnership, due to the asymmetry involved in relationships between rich and poor. Indeed, it can be seen that if, even by looking at a book, a child is aware that the book is donated from the West, that it symbolizes his own country’s inability to provide the material, and consequently the epistemological superiority of the west. Stirrat and Henkel notes that whilst altruistic or ‘pure’ gift-making can be founded on ‘universalistic ideals about the unity of humanity’, it is also ultimately a process governed and preserved by a ‘recognition of difference’ (Stirray and Henkel, 1977). It certainly seems that if books within librarians were Ghanaian in origin and context, the impact of this concern would be minimized.

b) Capabilities Approach

Young and Muller (2016) have argued in favor of the universal application of certain ‘powerful’ knowledge, which they consider to be more important and ultimately better extend capabilities. They suggest that we all intuitively understand that some knowledge is ‘better’ than others (ibid, 2016: 116), pointing to STEM subjects as the most ‘democratic’ and ‘the closest we can get to universal knowledge’, due to the ability to test this knowledge against the world, whereas cultural and traditional knowledge seems to be context-bound. However, returning to the capabilities approach, it seems important amidst this attempt to assert an objective set of criteria for the ‘bestness’, to reassert the value of individuals or communities determining that knowledge which they see most valuable. Young and Muller (2016) clash with Sen (1999) in suggesting that allowing individual preference holds little value in the case of curriculum planning and educational provision. Thus under their account, the most important thing with regards to the books transported to Akumadan is that they fall in line with the most recent scientific theories. Indeed, books being up to date with recent scientific theories is often a key criteria for book-shipping charities (e.g. Books for Africa, 2017).

There are some instances where it might be beneficial to the freedom and dignity of individuals for pupils to be aware of values that might be found within western fiction. Referencing Mill’s harm principle, most liberal thinkers agree that the preservation of freedoms should not lead to harm of others (Mill, 1859). Some knowledge can play a essential role in preventing harm, although real care needs to be taken over the labeling of positions as ‘western’ when they are rather ‘scientific’. For example, looking at a recent practice in Malawi where men named ‘hyenas’ were paid to have sex with girls when they reach puberty as a form of ritual ‘cleansing’ (BBC News, 2016), certain books might have been able to provide the girls and their families with frameworks to consider the unacceptability of this practice, and the scientific knowledge of how HIV can spread may have assisted them. However, quite clearly, just because books are African, it does not mean that they will not contain central ideas of human rights, medical knowledge of HIV and issues surrounding human dignity; indeed, these are topics of key priority in the current Ghanaian syllabus. Although Andreotti (2011) carefully highlights from a postcolonial perspective that human rights ‘cannot be presented as a “universally agreed” unproblematic set of values’, she does recognize its potency for protecting civilians from violence, particularly if the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is critically analysed and not viewed as a ‘an uncontested, ahistorical, depoliticized, and decontextualized’ framework (Andreotti, 2011: 212). Postcolonial insights provide a valuable tool for the critical analysis of abilities and/or rights approaches, due to the their focus on seeing all theoretical bases ‘through other eyes’ (Andreotti, 2011: 217).

Fundamentally, with respect to knowledge, it appears that the gains of understanding that are achieved by pupils reading some donated western fiction, outweigh the postcolonialist narratives and power relations that might be further entrenched by their readership. The fact still remains that just 1% of children in Ghana own 10 books (EFA Global Monitoring Report team, 2015:14). For this reason the EFA Report recommends that children are given further supplementary reading material that is more accessible for children to be able to self-teach themselves, through the association of words with illustrations in particular. This is exactly what western NGOs are providing at low cost through the imported fiction. However, the inclusion of knowledge relevant to the Ghanaian environment, alongside the western fiction, will clearly lead to further functionings desired by the Ghanaian child and their communities.

Our next post will explore identity ahead of coming to a conclusion on the issue, relating to EduSpots’ practice

Bibliography

Achebe, C. (2010) A British Protected Education, ‘Politics and Politicians of Language in African Literature’. Penguin Modern Classics.

Achebe, C. (1975) Morning Yet on Creation Day. Published by Anchor Press (1975)

Adjei, P. B. (2007) ‘Decolonising Knowledge Production: The Pedagogic Relevance of Gandhian Satyagraha to Schooling and Education in Ghana’. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue canadienne de l’Education, 30 (4), 1046-1067.

Alderson, P. (2016) ‘Critical Realism and Research Design and Analysis in Geographies of Children and Young People’ Geographies of Children and Young People: Methodological Approaches, 2016,Evans, R. and Holt, L. (eds). Singapore

Andreotti, V. (2011) Actionable postcolonial theory in education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ayer, A.J. (1953) Language, Truth and Logic, Penguin 2001 edition.

Benhabib, S. (1992) Situating the Self. Routledge

Bentham, J. (1789) Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Dover Publications (June 5, 2007)

Bhaskar, R. (1975) A Realist Theory of Science, Verso 2008.

Brezinger, M. (1997) Language contact and language displacement.

Chakrabarty, D. (2000) Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial thought and history. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Davison, C. (2017) ‘Ghana’s metamorphosis: an examination of the success of Nkrumah’s education policies in Ghana (1951-1966) as a tool for peace building.’ Essay submitted for Conflict, Fragility, and Education in May 2017.

Dei, G. J. S. (2002) Schooling and Education in Ghana. International Review of Education September 2002, Volume 48, Issue 5,

Dent, F.V. (2013) ‘A qualitative study of the academic, social, and cultural factors that influence students’ library use in a rural Ugandan village.’ University Libraries, Long Island University

Elbert, Fuegi and Lipeikaite. (2012) ‘Public libraries in Africa – agents for development and innovation? Current perceptions of local stakeholders (Electronic Information for Libraries)’ Sage.

Fanon, F. (1963) The Wretched of the Earth. Penguin, 2001.

Feyerabend, P. (1975) Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge. First edition in M. Radner & S. Winokur, eds., Analyses of Theories and Methods of Physics and Psychology, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1970.)

Fanon, F. (1967) Black Skin, White Masks. Grove Press; Revised edition 2008.

Freire, P. (1976) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Penguin 1996.

James, P. (2006) Globalism, Nationalism, Tribalism – Bringing Theory Back In. SAGE, London.

Kant, E. (1785) Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.; 3 edition (June 15, 1993)

Loomba, A. (2005). Colonialism-postcolonialism. Oxford: Routledge.

Lyotard, J-F. 1979. La condition postmoderne: rapport sur le savoir. Paris: Minuit.

Mackintosh, M. (2007) ‘Making Mistakes, Learning Lessons’, Primary Geographer 62. pp19-21

Maddox, B. (2008). ‘What good is literacy? Insights and implications of the capabilities approach’. Journal of Human Development 9,2, 185-206.

Mauss, Marcel. (1990) ‘The Gift: The Form of Research and Exchange in Archaic Societies’ (1990)

Maslow, A. H. (1943) ‘A Theory of Human Motivation.’ Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-96.

May, S. (2012) Language and Minority Rights. Routledge.

Mill, J.S. (1859) On Liberty Longman; New Ed edition, 1998.

Mill, J.S. (1863) Utilitarianism. Hackett Publishing Co, Inc; 2nd Revised edition edition (1 Mar. 2002)

McCowan, T. and Unterhalter, E. (2015) Education and international development: an introduction. London: Bloomsbury Academic Press

Mincer J. (1981) “Human Capital and Economic Growth” Working Paper 80, National Bureau of Economic Research. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w0803.pdf (accessed 20/05/2017).

Nussbaum, M. (2010) Not for profit. Why democracy needs the humanities Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nussbaum, M. (2011) Creating capabilities. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Nkrumah, K. (1964) Consciencism. Monthly Review Press (January 1, 1964)

Said, E. (1980) Orientalism. London: Routledge. pp 322-8 (‘Orientalism Now’ is also reproduced in Lauder, H. et al. (2006) Education, globalization and social change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.)

Said, E. (1993) ‘Representations of the Intellectual’ The 1993 Reith Lectures

Sen, A. (1999) Development as Freedom. OUP Oxford; New Ed edition (18 Jan. 2001)

Sen, A. (2009) The Idea of Justice. London: Allen Lane Penguin

Skutnabb-Kangas. (2000) Linguistic Genocide in Education – Or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights? Mah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Singer, P. (2011) Practical Ethics. Cambridge University Pres

Smock and Enchill. (1976) The Search for National Intergration in Africa

Spivak, G. C. (1988) ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’. In C. Nelson and L. Grossberg (Eds), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. x, 738 p). Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Some, M. P. (1994) ‘Of water and the spirit: Ritual magic and imitation in the life of an African Shaman.’ New York: Penguin Books.

Stirrat, R.L. and Henkel, H. (1997) ’The Development Gift: The Problem of Reciprocity in the NGO World’.

Takayama, K., Sriprakash, A., & Connell, R. (2015) ‘Rethinking Knowledge Production and Circulation in Comparative and International Education: Southern Theory, Postcolonial Perspectives, and Alternative Epistemologies.’ Comparative Education Review, 59(1).

Dangarembga, T. (1988) Nervous Conditions. Zimbabwe Pub. House (1988)

Tomasevski, K. (2001) Right to Education Primers No. 3: Human rights obligations: making education available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable. The Right to Education Project, Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA). Accessed at: http://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/Tomasevski_Primer%203.pdf

UNESCO, (2016) ‘Education for people and planet: Creating Sustainable Futures For All’. Global Education Monitoring Report, Paris, UNESCO – available on the UNESCO website.

Wa Thiong’o, N. (1986) Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Heinemann (2005)

Wa Thiong’o. (1969) Homecoming, London. P145

Wittgenstein, L. (1953) Philosophical Investigations. Wiley-Blackwell; 4th Revised edition edition (6 Nov. 2009)

Young, R. (2003) Postcolonialism: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young and Muller. (2016) Curriculum and the Specialization of Knowledge London Routledge.

Online Resources

African Storybook Project http://www.africanstorybook.org/index.php (Accessed 29/05/17)

The Danger of a Single Story, Adichie. Ted Talks, 2009.

https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story (Accessed 29/05/17)

Book Aid International: Kenya.

https://www.bookaid.org/countries/kenya/ (Accessed 29/05/17)

Books for Africa: About:

https://www.booksforafrica.org/about/about-bfa.html (Accessed 29/05/17)

Butler, E. ‘The Man Hired to Have Sex with Children’. BBC News, Malawi.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-36843769 (Accessed 29/05/17)

Davison, C. ‘Projects: Abofour Library’.

2 Comments

[…] of reading this analysis, please read part 1, part 2 and part 3 of this series of blog posts which offers an introduction to the topic and […]

[…] blog post draws the analysis from the previous posts exploring the elements of language, epistemology and identity together in some conclusions, ahead of relating this to EduSpots’ organisational […]