Ahead of reading this analysis, please read part 1 of this series of blog posts which offers an introduction to the topic and theories. The main image is taken from the Stanford University News website.

Through these posts, I exploring the issue of exporting/importing western fiction to Ghana or indeed other countries with a previous colonial relationship, with a view to informing EduSpots ongoing strategy in this area.

This post focuses upon language. Further posts on epistemology and identity will follow. Postcolonial theory and the capabilities approach are used as tools within the process of interrogation of key ideas and issues.

Postcolonialist analysis

Firstly, a postcolonial approach might suggest that providing books in English set in the western context entraps learners into taking on key aspects of western culture through the language itself. Language is a ‘form of life’ (Wittgenstein, 1953), echoed by Fanon’s statement that men possess ‘the world expressed and implied by that language’ (Fanon, 1967); therefore, whilst it may at face-value appear harmless for a child in Akumadan to read a book such as Enid Blyton’s Famous Five series, the children subconsciously take on a way of life which is not their own, immersed with cream teas and western notions of ‘adventure’. Adichie highlights how ‘impressionable and vulnerable’ children through absorbing stories – her own craving for ginger beer and concerns about the weather as a result of reading predominantly western books in Nigeria, were a clear clash with her own environment and cultural expectations (Adichie, 2009); indeed, pupils may find themselves craving western materialistic possessions that they may never be able to own.

Even if the books are printed in English in order to improve pupils’ understanding of the national language, it is certainly possible for African authors writing in English to communicate much of the ‘African experience’ through their writing (Thiong’o, 1983: 8). Many African authors suggest that the best way to fully communicate African ideas is to translate literally from the mother-tongue into the European language, suggesting that if the wording is kept as close as possible to the original expression, then the reader would best be able to ‘glean the social norms, attitudes and values of a people’ (Thiong’o, 1983: 8). Achebe points to the need for a ‘new English’, which is represents the African environment and voice (Achebe, 1975). African novels and folk stories have unique features such as representing character traits of humans through animals, as Alai highlights throughout his novel The Rhino in the Paddock (Alai, 2016). The methods through which Africans use to represent the characters that exist in their society are evidently vital to an understanding of that country’s social dynamics, and therefore it seems destructive to the child’s social education to not make such fiction in the library available to them.

In addition, the postcolonialist might argue that the imposition of English in itself is a continuing symbol of western dominance. Although many have suggested that there are advantages of minority languages being lost or demoted for the purpose of national development, many argue that there is a great cost of losing a local language (Howe, 1992), due to its role as a ‘carrier of culture’ (Thiong’o, 1983:13). Achebe felt that he had no choice but to write in English rather than a mother-tongue, despite him suggesting that it ‘produces a guilty feeling’ (Achebe, 1975). Fanon goes as far as to suggest that resisting colonial narratives and purging their influence upon the mind as a mentally cathartic practice (Fanon, 1963). Whilst in Ghana the national language did not profit a specific ethnic group, the decision to hold onto the use of English did reproduce inequality. Alexandre (1972) argues that it is possible to see a partition of class along linguistic lines in Africa (May 2012). Although it is important to note that local dialects are still taught in schools, and especially prioritized in the Primary years of education in Ghana, English it a vital ‘gatekeeper to positions of prestige’ within society (Alexandre, 1972), with many finding that they cannot access jobs in certain professions or own a business without being a skilled speaker of English.

Capabilities Approach

It might first be argued that the provision of Western reading material in English leads to the advancement of basic literacy in Ghana and that this would seem to enhance the capabilities enjoyed by individuals. Ghanaians would seemingly choose western books over no books at all. The postcolonial narrative vitally ignores the current desires of those in previously colonized countries to benefit from resources offered to them to improve their English, especially considering that all examinations at JHS, SHS and university level in Ghana are taken in English.

It is clear that libraries containing western fiction can help close the gap between rich and poor in literacy development (Frimpong, 2015), especially given that UNICEF reports that only 1% of Ghanaian children have more than 10 books in their home, and that 31% of Ghanaian adults are illiterate, with far higher figures in rural areas (UNICEF, 2017). Having access to books is in itself instrumental in developing ‘senses, imagination, and thought’ (Nussbaum). However, if pupils are not being presented which a choice of reading-based consumption, this appears to go against Nussbaum’s notion of ‘control over one’s environment’.

Indeed, on a practical level, those supporting the capabilities approach may argue that pupils’ capabilities may be limited by a detrimental impact of the books, due to issues concerning accurate usage of words. Meaning is established through nuanced use of language within ‘language games’ (Wittgenstein, 1953), and for this reason it vital that fiction is provided for children in which the usage of words is ‘acted out’ through situations relevant to their environment and communicates.

More importantly, there is evidence to suggest that books that focus on the western context and neglect African characters are less appealing to the reader than African fiction, and thus whilst the ‘capability’ to read might be open to pupils, this might not translate into a ‘functioning’ of reading. Mackintosh speaks of his experiences of returning to a school library he had supported in Malawi, and finding ‘piles of dust-covered books’. He came to a realization through talking to Gambian friends that the books were culturally inappropriate for the pupils, all featuring explicitly European characters (Mackintosh, 2007).

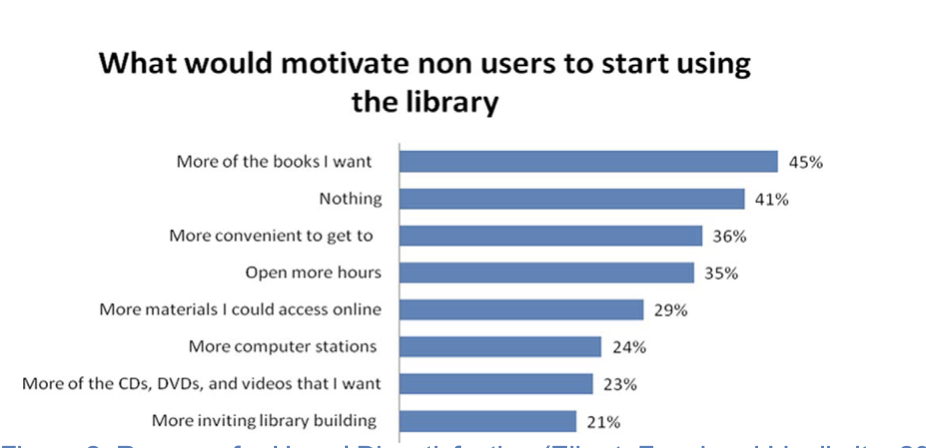

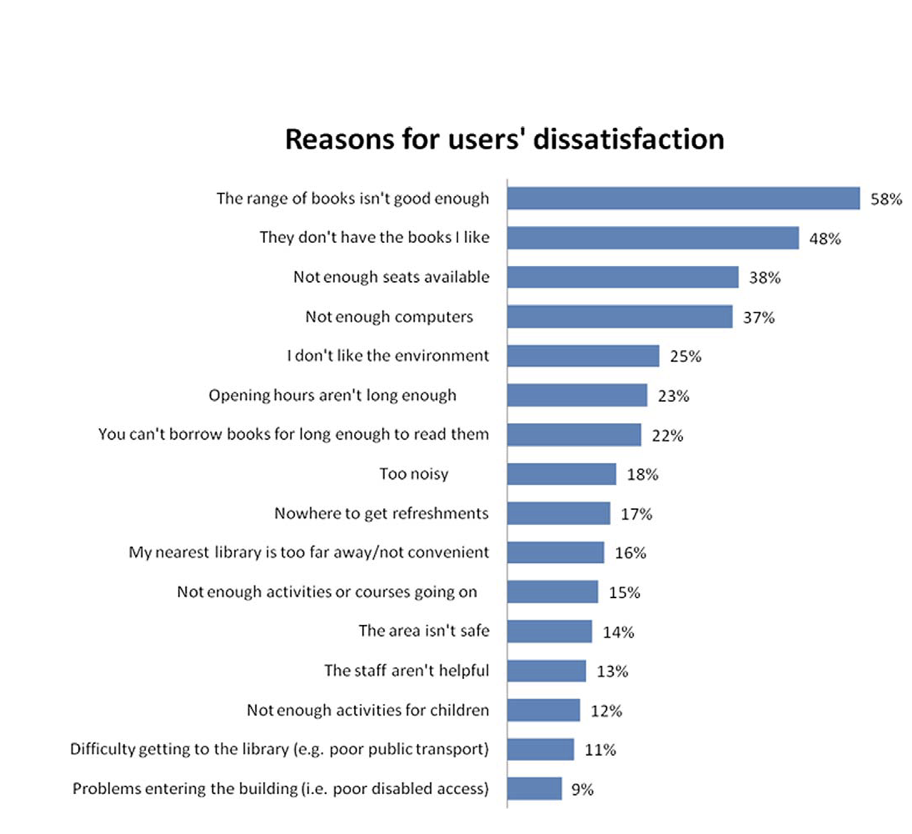

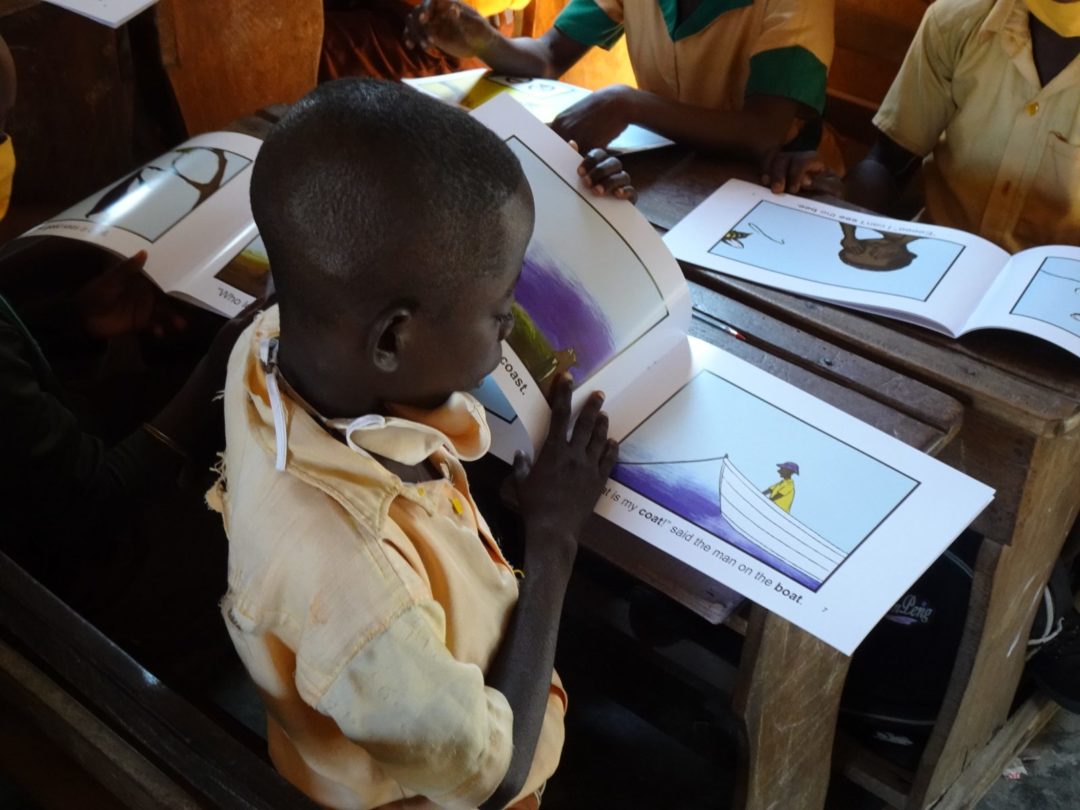

Research has indicated that libraries in Sub-Saharan Africa containing books that are relevant to context is the key motivator to the likely continued use of the library, with 45 percent of non-users identifying the provision of relevant reading material as a factor that would catalyse their use of the libraries, and 58% of users citing lack of sufficient range of books as the main reason for dissatisfaction (see Figure 1 and Figure 2 below, Elbert, Fuegi, and Lipeikaite, 2012). Whilst these figures do not necessarily point to a dissastification with western fiction, the statistics do show that choice is important to potential library uses. The preferences of individuals do seem better satisfied by the inclusion of African fiction as a choice. One boy in Dent’s study also highlights the improvement in behavior and performance in class as a result of improved understanding of English from reading books written in both Luganda and English from a local library in Uganda (Dent, 2013)

Coming next: Part 3: Exploring Epistemology

Bibliography

Achebe, C. (2010) A British Protected Education, ‘Politics and Politicians of Language in African Literature’. Penguin Modern Classics.

Achebe, C. (1975) Morning Yet on Creation Day. Published by Anchor Press (1975)

Adjei, P. B. (2007) ‘Decolonising Knowledge Production: The Pedagogic Relevance of Gandhian Satyagraha to Schooling and Education in Ghana’. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue canadienne de l’Education, 30 (4), 1046-1067.

Alderson, P. (2016) ‘Critical Realism and Research Design and Analysis in Geographies of Children and Young People’ Geographies of Children and Young People: Methodological Approaches, 2016,Evans, R. and Holt, L. (eds). Singapore

Andreotti, V. (2011) Actionable postcolonial theory in education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ayer, A.J. (1953) Language, Truth and Logic, Penguin 2001 edition.

Benhabib, S. (1992) Situating the Self. Routledge

Bentham, J. (1789) Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Dover Publications (June 5, 2007)

Bhaskar, R. (1975) A Realist Theory of Science, Verso 2008.

Brezinger, M. (1997) Language contact and language displacement.

Chakrabarty, D. (2000) Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial thought and history. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Davison, C. (2017) ‘Ghana’s metamorphosis: an examination of the success of Nkrumah’s education policies in Ghana (1951-1966) as a tool for peace building.’ Essay submitted for Conflict, Fragility, and Education in May 2017.

Dei, G. J. S. (2002) Schooling and Education in Ghana. International Review of Education September 2002, Volume 48, Issue 5,

Dent, F.V. (2013) ‘A qualitative study of the academic, social, and cultural factors that influence students’ library use in a rural Ugandan village.’ University Libraries, Long Island University

Elbert, Fuegi and Lipeikaite. (2012) ‘Public libraries in Africa – agents for development and innovation? Current perceptions of local stakeholders (Electronic Information for Libraries)’ Sage.

Fanon, F. (1963) The Wretched of the Earth. Penguin, 2001.

Feyerabend, P. (1975) Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge. First edition in M. Radner & S. Winokur, eds., Analyses of Theories and Methods of Physics and Psychology, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1970.)

Fanon, F. (1967) Black Skin, White Masks. Grove Press; Revised edition 2008.

Freire, P. (1976) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Penguin 1996.

James, P. (2006) Globalism, Nationalism, Tribalism – Bringing Theory Back In. SAGE, London.

Kant, E. (1785) Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.; 3 edition (June 15, 1993)

Loomba, A. (2005). Colonialism-postcolonialism. Oxford: Routledge.

Lyotard, J-F. 1979. La condition postmoderne: rapport sur le savoir. Paris: Minuit.

Mackintosh, M. (2007) ‘Making Mistakes, Learning Lessons’, Primary Geographer 62. pp19-21

Maddox, B. (2008). ‘What good is literacy? Insights and implications of the capabilities approach’. Journal of Human Development 9,2, 185-206.

Mauss, Marcel. (1990) ‘The Gift: The Form of Research and Exchange in Archaic Societies’ (1990)

Maslow, A. H. (1943) ‘A Theory of Human Motivation.’ Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-96.

May, S. (2012) Language and Minority Rights. Routledge.

Mill, J.S. (1859) On Liberty Longman; New Ed edition, 1998.

Mill, J.S. (1863) Utilitarianism. Hackett Publishing Co, Inc; 2nd Revised edition edition (1 Mar. 2002)

McCowan, T. and Unterhalter, E. (2015) Education and international development: an introduction. London: Bloomsbury Academic Press

Mincer J. (1981) “Human Capital and Economic Growth” Working Paper 80, National Bureau of Economic Research. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w0803.pdf (accessed 20/05/2017).

Nussbaum, M. (2010) Not for profit. Why democracy needs the humanities Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nussbaum, M. (2011) Creating capabilities. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Nkrumah, K. (1964) Consciencism. Monthly Review Press (January 1, 1964)

Said, E. (1980) Orientalism. London: Routledge. pp 322-8 (‘Orientalism Now’ is also reproduced in Lauder, H. et al. (2006) Education, globalization and social change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.)

Said, E. (1993) ‘Representations of the Intellectual’ The 1993 Reith Lectures

Sen, A. (1999) Development as Freedom. OUP Oxford; New Ed edition (18 Jan. 2001)

Sen, A. (2009) The Idea of Justice. London: Allen Lane Penguin

Skutnabb-Kangas. (2000) Linguistic Genocide in Education – Or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights? Mah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Singer, P. (2011) Practical Ethics. Cambridge University Pres

Smock and Enchill. (1976) The Search for National Intergration in Africa

Spivak, G. C. (1988) ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’. In C. Nelson and L. Grossberg (Eds), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. x, 738 p). Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Some, M. P. (1994) ‘Of water and the spirit: Ritual magic and imitation in the life of an African Shaman.’ New York: Penguin Books.

Stirrat, R.L. and Henkel, H. (1997) ’The Development Gift: The Problem of Reciprocity in the NGO World’.

Takayama, K., Sriprakash, A., & Connell, R. (2015) ‘Rethinking Knowledge Production and Circulation in Comparative and International Education: Southern Theory, Postcolonial Perspectives, and Alternative Epistemologies.’ Comparative Education Review, 59(1).

Dangarembga, T. (1988) Nervous Conditions. Zimbabwe Pub. House (1988)

Tomasevski, K. (2001) Right to Education Primers No. 3: Human rights obligations: making education available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable. The Right to Education Project, Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA). Accessed at: http://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/Tomasevski_Primer%203.pdf

UNESCO, (2016) ‘Education for people and planet: Creating Sustainable Futures For All’. Global Education Monitoring Report, Paris, UNESCO – available on the UNESCO website.

Wa Thiong’o, N. (1986) Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Heinemann (2005)

Wa Thiong’o. (1969) Homecoming, London. P145

Wittgenstein, L. (1953) Philosophical Investigations. Wiley-Blackwell; 4th Revised edition edition (6 Nov. 2009)

Young, R. (2003) Postcolonialism: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young and Muller. (2016) Curriculum and the Specialization of Knowledge London Routledge.

Online Resources

African Storybook Project http://www.africanstorybook.org/index.php (Accessed 29/05/17)

The Danger of a Single Story, Adichie. Ted Talks, 2009.

https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story (Accessed 29/05/17)

Book Aid International: Kenya.

https://www.bookaid.org/countries/kenya/ (Accessed 29/05/17)

Books for Africa: About:

https://www.booksforafrica.org/about/about-bfa.html (Accessed 29/05/17)

Butler, E. ‘The Man Hired to Have Sex with Children’. BBC News, Malawi.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-36843769 (Accessed 29/05/17)

Davison, C. ‘Projects: Abofour Library’.

3 Comments

[…] of reading this analysis, please read part 1 and part 2 of this series of blog posts which offers an introduction to the topic and […]

[…] of reading this analysis, please read part 1, part 2 and part 3 of this series of blog posts which offers an introduction to the topic and […]

[…] blog post draws the analysis from the previous posts exploring the elements of language, epistemology and identity together in some conclusions, ahead of relating this to EduSpots’ […]